Several of my Posts have been to expose the absurdity of the diet-cholesterol-heart hypothesis, which has dominated healthy diet advice during more than half a century.

The relationships between diet, cardiovascular disease, and death are topics of major public health importance, and subjects of great controversy.

In European and North American countries, the most enduring and consistent diet advice is to restrict saturated fatty acids, by replacing animal fats with vegetable oils and complex carbohydrates

During the past fifty years there has been little questioning of the theory; the advice to reduce dietary cholesterol and fats continues unchecked. However there have been many studies that have have shown that the diet component of the theory is not sustainable, but the results of these studies have failed to make an impact on popular belief.

The view of a growing number of scientists is that advice to restrict saturated fatty acids is “largely based on selective emphasis on some observational and clinical data, despite the existence of several randomised trials and observational studies that do not support these conclusions”.

The PURE study

A large study was recently published in The Lancet. It is known as the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. It investigated the health outcomes of 135,335 individuals aged 35–70 years of age, followed for an average of 7.4 years.

The study was undertaken in 18 countries. These included 3 high-income (Canada, Sweden, and United Arab Emirates), 11 middle-income (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Iran, Malaysia, occupied Palestinian territory, Poland, South Africa, and Turkey) and 4 low-income countries (Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Zimbabwe).

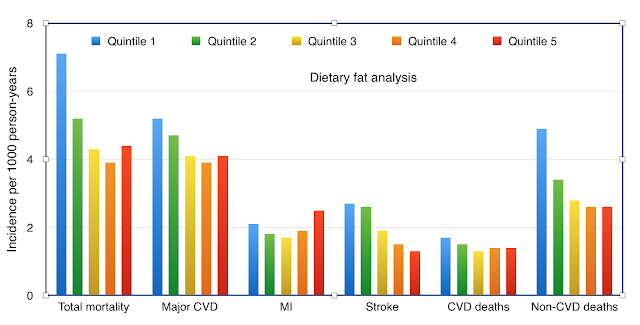

Dietary patterns were recorded in detail. The subjects were divided into five groups (quintiles) for diet category, Quintile 1 being the lowest 20% of specific intake, and Quintile 5 the highest 20% intake.

The study documented 5796 deaths and 4784 major cardiovascular disease events. The main morbidity/mortality categories were total deaths, cardiovascular (CVD) deaths, major CVD events, myocardial infarction (heart attack, MI), and stroke.

Findings

The study was complex in that a great deal of data were recorded and presented in the Lancet paper. I cannot present all the data in this review, but I will concentrate on the two major diet groups of saturated fat and carbohydrate.

The study does not record the absolute consumption of food and its constituents, but just proportions. In other words, if fat intake is reduced then the proportion of carbohydrate inevitably increases, and vice versa.

Dietary Fats

In the “rainbow” Figure 1, we can see on the horitontal x-axis of the graph the 6 categories of morbidity and mortality. Each category or group needs to examined separately. Within each group are the quintiles of fat intake, the lowest on the left and the highest on the right. Each quintile has its own colour, and the legend is shown at the top.

The vertical y-axis indicates the incidence of deaths or major events, incidence per 1000 person-years.

Let us first look at “total mortality”, the first group. shows a decline in mortality with increasing fat intake, from 7 events per 1000 person-years in quintile 1 to 4.2 events in quintile 6.

We can also see the same pattern in respect of “major CVD”, “stroke”, and “non-CVD deaths”. There is no effect on MI and CVD deaths.

It appears that there is no detriment to a high proportion of the diet being saturated fats, and there is a significant advantage in respect of total and non-cardiovascular mortality. This is not what we have been led to expect.

Dietary carbohydrate

Now we will turn to dietary carbohydrate and its relationship to mortality and cardiovascular illness.

This is summarised in Figure 2, which looks like Figure 1 but the results different.

|

| Figure 2. Carbohydrate intake association with mortality and morbidity |

Within the group of “total mortality” we can see that as the proportion of carbohydrate increases from quintile 1 to 5, the mortality rate increases.

There is a similar but less significant pattern for major CVD events, stroke and non-CVD deaths.

There is a similar but less significant pattern for major CVD events, stroke and non-CVD deaths.

There are no effects on MI and CVD deaths.

In respect of total mortality, non-cardiovascular deaths and major CVD events, a high proportion of carbohydrates in the diet is not a good thing.

In respect of total mortality, non-cardiovascular deaths and major CVD events, a high proportion of carbohydrates in the diet is not a good thing.

Conclusions

During the past 50 years dierty advice reduce the fat content of our diet has inevitably increased the carohydrate proportion. Therefore advice to reduce fat intake, and therefore increasing proportion from carbohydrate, is likely to have increased deaths and major events, the opposite of the intention of public health advice.

The dietary component of the diet–cholesterol–heart hypothesis has perhaps been quiety side-lined by the cholesterol “experts”. But the cholesterol – heart component continues and despite evidence to the contrary it underpins the pharmacological “treatment of cholesterol”. Cholesterol now seems to be a disease in itself.

In the PURE study a higher proportion of total fat intake and each type of fat was associated with a lower risk of total mortality .

Higher saturated fat intake was associated with lower risk of stroke.

Total fat and saturated and unsaturated fats were not significantly associated with risk of myocardial infarction or cardiovascular disease mortality.

Higher carbohydrate intake was associated with an increased risk of total mortality but not with the risk of cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular disease mortality.

The authors conclude with this statement:

“Global dietary guidelines should be reconsidered in light of the consistency of findings from the present study, with the conclusions from meta-analyses of other observational studies and the results of recent randomised controlled trials.”

Will we see any change of official diet policy?

Will we see any change of official diet policy?