|

| The Organ Grinder - L S Lowry |

Dramatic headlines sell newspapers but might misinform the readers. Risks are generally greatly exaggerated and statistics are far from clear.

(Between normal weight and obesity is called "overweight", that is excess weight short of obesity. It is this that is apparently "killing millions".)

I must say that I have been unaware of millions being killed by anything at present, certainly not by being a bit overweight and not actually obese.

I must say that I have been unaware of millions being killed by anything at present, certainly not by being a bit overweight and not actually obese.

It goes on:

" Nearly two-thirds of adults in Britain weigh too much "

Do you know – all these two thirds are going to die, and so are their slim fellow-citizens, whose "virtue" of slimness will not give them immortality. Who says that they "weigh too much"? Is it doing them any harm? On what is the standard based? And when was it established?

Another comment:

" Experts say many people failing to understand risks "

Perhaps the experts fail to understand risks. How is it that so many people are living so much longer? This is not disputed.

Let us look further at the influence of body weight on survival.

Let us look further at the influence of body weight on survival.

Framingham

In previous Posts I have referred to the Framingham study in the USA. The study is based on a small town in Massachusetts and it was initiated in 1948. It has followed 5209 participants aged between 28 and 62 years, recording the development of illness and death during the past 70 years . It is an observational programme that has collected much useful information.

I have previously drawn attention to the 40 year study of cholesterol levels of the population. The conclusion reached is that “After the age of 50 years there is no increased overall mortality with either high or low serum cholesterol levels.” Despite its profound importance, this finding never entered collective consciousness. It is the cholesterol truth that has been kept away from the public and the media.

I have previously drawn attention to the 40 year study of cholesterol levels of the population. The conclusion reached is that “After the age of 50 years there is no increased overall mortality with either high or low serum cholesterol levels.” Despite its profound importance, this finding never entered collective consciousness. It is the cholesterol truth that has been kept away from the public and the media.

Between 1951 and 2011, 1058 participants in Framingham suffered from a stroke.

Most episodes of stroke are ischaemic, the result of cerebral infarction, the occlusion of blood supply to part of the brain. This is usually due to narrowing of an artery by the process of atherosclerosis. It is occasionally due an embolus from or via the heart. The other cause of stroke is a cerebral haemorrhage, due to the rupture of an artery, usually from an asymptomatic aneurysm. It is difficult to distinguish the two forms of stroke clinically, but CT scanning will show a haemorrhage. The absence of haemorrhage on CT scan leads to the diagnosis of ischaemic stroke. It is this group that is the subject of a study from Framingham published this year.

Most episodes of stroke are ischaemic, the result of cerebral infarction, the occlusion of blood supply to part of the brain. This is usually due to narrowing of an artery by the process of atherosclerosis. It is occasionally due an embolus from or via the heart. The other cause of stroke is a cerebral haemorrhage, due to the rupture of an artery, usually from an asymptomatic aneurysm. It is difficult to distinguish the two forms of stroke clinically, but CT scanning will show a haemorrhage. The absence of haemorrhage on CT scan leads to the diagnosis of ischaemic stroke. It is this group that is the subject of a study from Framingham published this year.

The purpose of this particular study was to investigate the influence of body weight on the outcome of stroke. The outcome measure was survival at ten years. In addition to following the outcome of those who had suffered stroke, age-matched controls from Framingham were also followed.

BMI (Body Mass Index)

In the initial presentation of data the subjects were divided into two groups based on BMI, the simple measure of obesity. The two groups were those with BMI less than 25 (normal) and those with BMI 25 or greater (overweight or obese).

BMI is a number based on weight and height: weight Kg / height in metres squared. Between 18 and 25 is regarded as “normal”. "Normal" is arbitrary and thus judgmental. We see from the headline above that two-thirds of UK adults being so defined as overweight is not a statistical normality.

Effect of BMI on survival

Figure 1 shows the 10 year survival rates of the control groups, who had not had a stroke. They were divided into those with BMI less than 25 and those with BMI 25 or greater. It can be seen clearly that there is no significant difference. The two survival lines are very close together, indistinguishable. This is an important finding from a large and well-constructed study, but the information appears to have been hidden from public scrutiny.

The main purpose of the study was to investigate the outcome after a stroke, and we can see this in Figure 2.

In Figure 2 we see the addition of the survival lines for the people who had experienced a stroke. They are divided into two groups depending on BMI.

It is not surprising that the life expectancy of those who had a stroke was about half that of those who had not experienced a stroke, the control group. Having had a stroke is clearly a serious risk indicator of an early death.

It is not surprising that the life expectancy of those who had a stroke was about half that of those who had not experienced a stroke, the control group. Having had a stroke is clearly a serious risk indicator of an early death.

Figure 3 show just the stroke survivors. Following a stroke there is a significant difference in the 10 year life expectancy, depending on the BMI. Here we encounter what has been recognised in previous studies and called “the obesity paradox”.

The life expectancy is much better in the obese group (BMI 25+, green line) compared to their slimmer counterparts (BMI <25, blue line). This is not what conventional wisdom would have led us to believe.

The life expectancy is much better in the obese group (BMI 25+, green line) compared to their slimmer counterparts (BMI <25, blue line). This is not what conventional wisdom would have led us to believe.

The study also subdivided the participants into the sub-categories of:

“normal weight” (BMI less than 25),

“low overweight” (BMI 25 to less than 27.5),

“high overweight” (BMI 27.5 to less than 30),

“low obesity”, (BMI 30 to less than 32.5),

“high obesity” (BMI 32.5 or greater).

“normal weight” (BMI less than 25),

“low overweight” (BMI 25 to less than 27.5),

“high overweight” (BMI 27.5 to less than 30),

“low obesity”, (BMI 30 to less than 32.5),

“high obesity” (BMI 32.5 or greater).

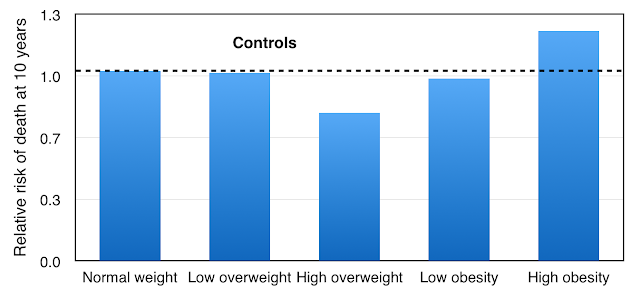

Once again we can first look at the control group, those without stroke, and we can see the results in Figure 4. A low column height is a good thing.

The normal weight group has death rate at 10 years standardised at 1.0. Low overweight has a similar risk of death. The lowest risk of death is with the high overweight group, a relative risk reduction of 0.78. This is a 20% reduction of risk of death at 10 years.

Low obesity is little different from normal weight, but high obesity gives a survival disadvantage with a relative risk of 1.21 (21% increased risk of death at 10 years).

These results, taken from a sample of the general population of Framingham, are very interesting: despite what we are told in the headlines at the top of this Post, there are advantages in being overweight, but not if BMI is above 32.5.

Survival after stroke

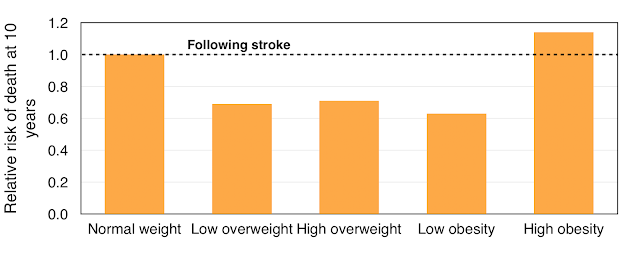

We can now look at the data for those who had experienced a stroke, shown in Figure 5. Again a low column height is a good thing.

The death rate at 10 years for normal weight individuals is standardised as 1.0. We see a survival advantage in those with low overweight, high overweight, and low obesity – that is with people with BMI between 25 and 32.5. With “low obesity” there is a death risk reduction of almost 40%.

If BMI is greater than 32.5 there is a survival disadvantage, with an increase in risk of death at 10 years of just under 20%.

We have been looking at observations. Explanation is something different and I have no intention of making a guess. There is so much about body weight and its controls that we simply do not understand.

In respect of the survival advantage of overweight and mild obesity, there is no explanation in respect of characteristics of the population groups (see Figure 6).

In respect of the survival advantage of overweight and mild obesity, there is no explanation in respect of characteristics of the population groups (see Figure 6).

|

| Figure 6: Characteristics of Framingham obesity study |

For example it is the normal weight group that has the highest proportion of severe strokes. This group also has the highest proportion of smokers. The obese group has the highest incidence of diabetes, as would be expected, but surprisingly the lowest incidence of coronary heart disease.

The lower risk of death in the overweight groups as shown in Figure 5 cannot be explained by the table in Figure 6 or other factors in the fuller analysis of risk factors.

The lesson from this first-class study study is that moderate obesity appears to give a survival advantage following a stroke. In the control population obesity does not give a survival disadvantage.

Previous study of BMI and survival

It has been shown but not extensively publicised that BMI and measures of adiposity do not in themselves predict cardiovascular disease. This was published in The Lancet, the work being funded by the British Heart Foundation and the UK Medical Research Council.

I have shown in a previous Post further evidence that mild to moderate obesity does not give a survival disadvantage, but some advantage. The details can be seen in Figure 7.

The graph lines indicate risk of death based on BMI for two groups, ages 50 years (green line) and 70 years (blue line). As would be expected the death rates were higher in the 70 year-olds.

But in both age groups the lowest death rates were in those people with BMI between 20 and 30. There was a gradual increase of death rate as the BMI increased to 45, the point of gross obesity, a dangerous condition. However the death rate rose steeply in the other direction with BMI less than 20.

The best life expectancy was in those considered to be overweight or mildly obese. Our obsession with thinness should come to an end.

The best life expectancy was in those considered to be overweight or mildly obese. Our obsession with thinness should come to an end.

Overweight is an advantage after heart surgery

A recent study from the University of Leicester, UK, was led by Professor Gavin Murphy and its results were published in the European Heart Journal. The study concerned the early mortality following heart surgery, and it has been given particularly detailed coverage by the academic press.

The study was of 401,227 adults, and a review of 557,720 patients from 13 countries. Average age was 59 years and 27% were women.

|

| Figure 8: Body weight and risk of death after heart surgery |

The results can be seen in Figure 8. The risk of death was highest at 8.5% in the underweight group. It was 4.4% in the "normal" weight group but even lower at 2.7% and 2.8% in the overweight and obese groups. It was very surprisingly low at 3.3% in the obese patients who were considered to be at particularly high risk.

There have been attempts to disregard or explain away these findings but this was not the purpose of the study. Explanation must wait. There are of course attempts to find faults that might invalidate the findings, as we expect all categories of excess weight to be dangerous, but such attempts have not been successful. The research was very well controlled and those with low weight appear to be at the greatest risk.

Conclusion

We can conclude that there is much about body weight that we do not understand. Gross obesity is to be avoided, not only because of death rate but also because of serious morbidity, especially musculoskeletal problems and reduced mobility.

However we cannot conclude that thinness is to be applauded. At the present time we have two concurrent epidemics. The first is that of long life expectancy, a serious social problem. It is a to a major extent the consequence of the end of the epidemic of coronary heart disease. The other epidemic is allegedly that of obesity. Perhaps this so-called "epidemic" is an important factor leading us to be living longer.

However we cannot conclude that thinness is to be applauded. At the present time we have two concurrent epidemics. The first is that of long life expectancy, a serious social problem. It is a to a major extent the consequence of the end of the epidemic of coronary heart disease. The other epidemic is allegedly that of obesity. Perhaps this so-called "epidemic" is an important factor leading us to be living longer.

BMI between 20 and 30 seems to be about right, and the evidence is clear.

References:

Journal of the American Heart Association doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004721

Lancet. 2011 Mar 26;377(9771):1085-95. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60105-0.

New Scientist 2014; Volume 222, Number 2967, Page 44.

Eur Heart J (2017) 38 (23): 1786-1787.

DOI:

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteYou are correct, and thank-you for the comment. Now corrected -"moderate obesity appears to give a survival advantage following a stroke."

ReplyDeleteGood news for we oldies David

ReplyDeleteI wonder however whether results for 'normal weight' are adversely skewed. I can think of several instances of deceased acquaintances who lost a tremendous amount of weight before their demise. Are some normal weight participants in trials already in decline?