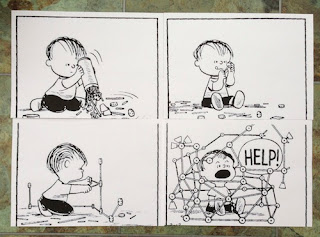

In so many aspects of life and management, what seems to be a good idea can grow and stifle the best of human initiatives.

There was a time, until about 20 years ago, when clinical medicine was decentralised. A hospital was composed of clinical teams which were located on specific wards. The consultant and the ward sister led a team, with a number of trained and student nurses, together with doctors in training grades. They knew each other and worked together. They cared for their patients in a personal and humane way.

But some teams did not work very well, and this is inevitable in all forms of human activity. This sometimes came to public attention through the press. The Government Department of Health had to bear responsibility. Something had to be done to raise the standards of these few outliers but this has resulted in a heavily bureaucratic and often nation-wide approach. Clearly defined instructions, pathways, would be introduced so that the process of care, not the outcome, could be clearly monitored and audited by a new bureaucracy called clinical governance. And this has become the problem of clinical audit: it is concerned with process, which is easily measured against predetermined pathways, and not outcome, which is less easily defined. We always measure what it is easy to measure rather than what it is most useful to measure.

Close clinical teams became a thing of the past, as is much of personalised medicine. The changes were of course introduced for the best of motives, but as seen from far away from the bedside and introduced by a management that was usually remote and unknown to the clinical workforce. It was clearly imposition from above, not a good way of encouraging excellence in a people and professional organisation such as a hospital.

The Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP), like all pathways, stopped people from thinking. Rather than the ward staff discussing the care needs of an patient who would be close to the end of life, and developing a personalised management plan, the ward staff would simply reach for another copy of the LCP (a 34-page document) from off the shelf. "There we are, simple, no thinking, no debate, no chance of error of process, beyond criticism by management - just write the patient's name on the front."

Individual doctors and nurses, and managers, are usually sensible, but put them in committees especially distant from the place of work, and they seem to lose all reason. The LCP, the bureaucratisation of dying, has been an episode of madness. Its removal is a burden lifted and an opportunity for improved and personalised patient care.

We all hope to die peacefully and the LCP was intended as a way to achieve this. But it was a top-down and not a bottom-up approach. For that reason it has become a great disappointment. The staff who wrote it are to be congratulated for their time, effort and vision. It was the imposition that has led to failure. From now on we must remember the useful messages written into the document, and we must develop care plans of our own at the bedside.

Lol, at first I thought this post is about Liverpool football club and I just got super excited but it was not. Lol, a great share by the way.

ReplyDeleteThanks for contributing your important time to post such an interesting & useful collection of knowledgeable resources that are always of great need to everyone tik tok video

ReplyDelete